Cardiac Electrophysiology

Cardiac electrophysiology is the science of researching, diagnosing, and treating the electrical activities of the heart. Our heart doctors are skilled in diagnosing and treating ablation, atrial fibrillation, and aflutter through the necessary procedures and devices, such as pacemakers and therapy defibrillators.

Learn more about specific heart conditions and treatments below.

Ablation for Arrhythmias

Catheter ablation is a procedure that uses radiofrequency energy (similar to microwave heat) to destroy a small area of heart tissue that is causing rapid and irregular heartbeats. Destroying this tissue helps restore your heart’s regular rhythm. The procedure is also called radiofrequency ablation.

- Catheter ablation is used to treat abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmias) when medicines are not tolerated or effective.

- Medicines help to control the abnormal heart tissue that causes arrhythmias. Catheter ablation destroys the tissue.

- Catheter ablation is a low-risk procedure that is successful in most people who have it.

- This procedure takes place in a special hospital room called an electrophysiology (EP) lab or a cardiac catheterization (cath) lab. It takes 2 to 4 hours.

Special cells in your heart create electrical signals that travel along pathways to the chambers of your heart. These signals make the heart’s upper and lower chambers beat in the proper sequence. Abnormal cells may create disorganized electrical signals that cause irregular or rapid heartbeats called arrhythmias. When this happens, your heart may not pump blood effectively and you may feel faint, short of breath, and weak. You may also feel your heart pounding.

Medicines to treat rapid and irregular heartbeats work very well for most people. But they don’t work for everyone, and they may cause side effects in some people. In these cases, doctors may suggest catheter ablation.

The procedure is used most often to treat a condition called supraventricular tachycardia, or SVT, which occurs because of abnormal conduction fibers in the heart. Catheter ablation is also used to help control other heart rhythm problems such as atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation. Catheter ablation destroys the abnormal tissue without damaging the rest of the heart.

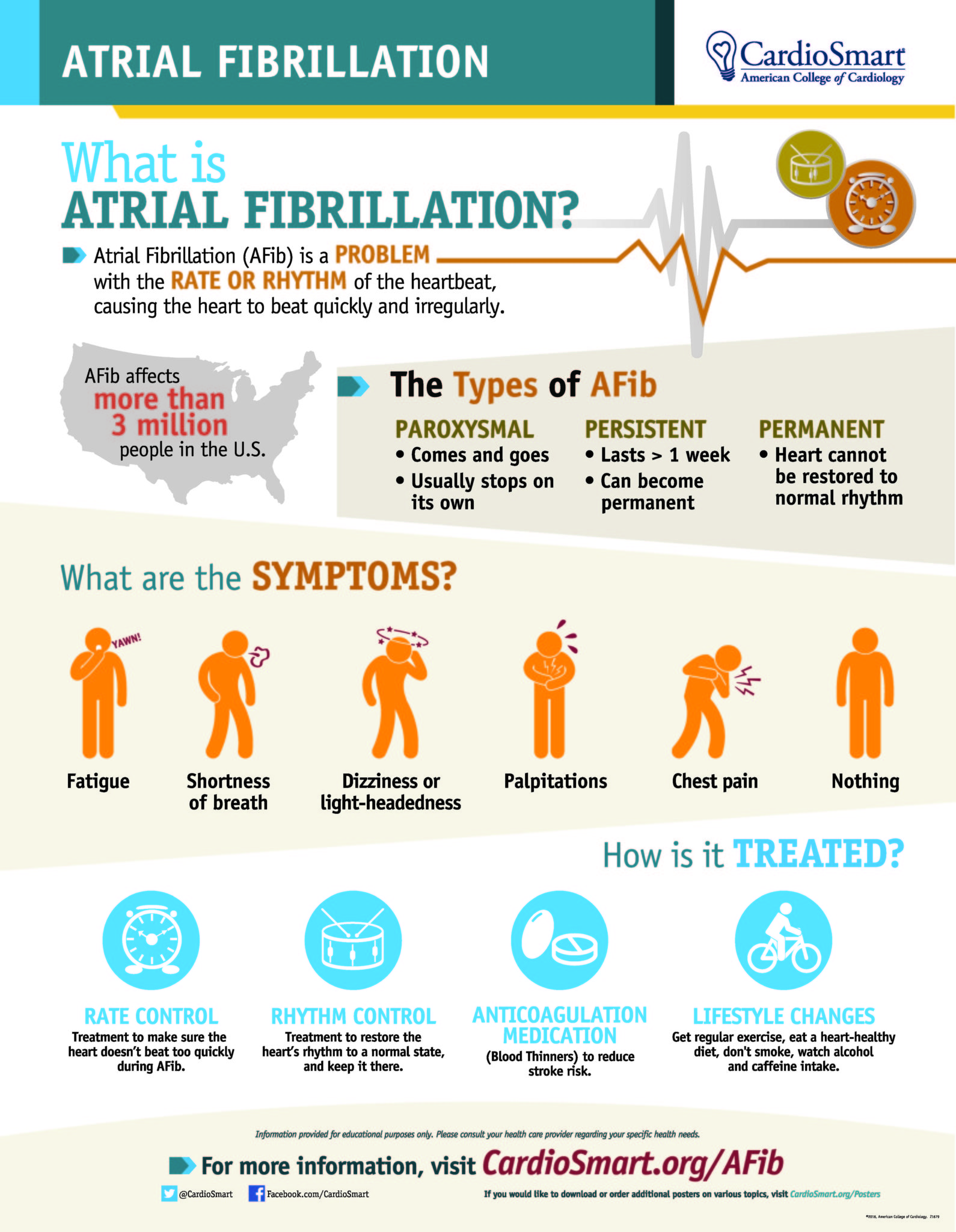

Atrial Fibrillation

Under normal circumstances, the human heart pumps to a strong and steady beat — in fact, more than 100,000 heartbeats each day! But if you have atrial fibrillation, or AFib, the heart doesn’t always beat or keep pace the way it should. Many people with AFib say they can feel their heart racing, fluttering, or skipping beats. AFib is the most common heart rhythm disorder (arrhythmia). A major concern with AFib is that it also makes blood clots in the heart that can travel and cause strokes or block flow to other critical organs. In fact, people with this condition are five times more likely to have a stroke than people without the condition. It can also lead to heart failure. But finding and treating AFib early on can help you avoid these problems.

Your heart’s electrical system tells your heart when to contract and pump blood to the rest of your body. With AFib, these electrical impulses don’t work the way they should, short-circuiting in a sense. As a result, the heart beats too quickly and irregularly.

Your heart’s electrical system tells your heart when to contract and pump blood to the rest of your body. With AFib, these electrical impulses don’t work the way they should, short-circuiting in a sense. As a result, the heart beats too quickly and irregularly.

AFib is sometimes called a quivering heart. That’s because the two upper parts of the heart (called the atria) quiver. When this happens, the normal communication between the upper and lower chambers of the heart is disrupted and becomes very disorganized. Because of this, many people with AFib feel zapped of energy fairly quickly or notice being out of breath simply walking up one flight of stairs. That’s because you may not be getting enough oxygen; the heart isn’t able to squeeze enough nutrient-rich blood out to the body.

The 3 Types of AFib:

- Paroxysmal: Comes and goes and generally stops on its own

- Persistent: Lasts more than a week and can become permanent

- Permanent: The heart’s normal rhythm can’t be restored

Some cases of AFib are due to a heart valve problem, while some are not.

If you have AFib, you’re not alone. It’s the most common type of irregular heartbeat, affecting more than 3 million Americans. If untreated, it can lead to blood clots, stroke, and heart failure.

Because your heartbeat is out of sync, blood can collect in the chambers of the heart. When this happens, blood clots can form and can travel to the brain, causing a stroke. Strokes related to AFib tend to be more severe and deadly.

Several factors make AFib more likely.

- Older age, although it can happen at any age

- Conditions that place added strain on the heart, including:

- high blood pressure

- previous heart attack

- heart surgery

- valve disease

- heart failure

- Other illnesses such as obesity, sleep apnea, or hyperthyroidism

- Family history

- Drinking too much alcohol (routinely having 3 or more drinks a day or binge drinking)

Episodes of AFib are often triggered by certain activities. These may include:

- Heavy alcohol use

- Too much caffeine or other stimulants

- Periods of severe stress

- the stress of the body fighting infection

- the stress of recent surgery

Pay attention to what might make symptoms of AFib worse, so that you can share this information with your health care team.

Some people with AFib don’t have any symptoms. Those who do may report:

- Heart palpitation – a thumping or racing heart, fluttering, or skipping beats

- Feeling unusually tired or fatigued

- Unexplained shortness of breath

- Dizziness or fainting spells

- Chest pain (angina)

Detecting an abnormal heart rhythm

To find out if you have AFib, your doctor will likely rely on a combination of:

- Your medical history and physical exam

- Results from an electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG) – a test that records your heart’s electrical activity and shows deviations

- Other methods to monitor your heart’s rhythm, if needed. Additional tests may include:

- Wearing a Holter monitor, essentially a portable EKG to measure and record your heart’s activity for 24 hours.

- Using an event monitor that, with a push of a button, allows you to record what is happening when you feel symptoms such as chest pain, dizziness, or palpitations. Electrodes are placed on your chest and are connected by wire leads to the recording device. You generally will wear this for one month.

- Having an echocardiogram, an ultrasound that takes pictures of the heart and measures the chambers and how well it is pumping.

Sometimes, people are diagnosed with AFib after going to the hospital emergency department and are “in AFib.”

The good news is that with the right treatment, you can live a good life with AFib. But you need to be in tune with your heart and body. Untreated, atrial fibrillation can lead to blood clots, stroke, and other heart-related problems, including heart failure.

Your treatment will likely depend on:

- Your age

- Your symptoms and the frequency of episodes

- Whether your heart rate is under control

- Your risk for stroke

- Other medical conditions, including if you already have heart disease

Treatment of AFib focuses on lifestyle changes and either rate control or rhythm control. Therapies to prevent blood clots and stroke are also important.

Lifestyle changes may include:

- Eating a heart-healthy diet full of fresh fruits and vegetables, fiber-rich foods, lean meats and fish, and unsaturated fats like olive oil

- Limiting alcohol and caffeine

- Exercising regularly – aim to get 30 minutes of physical activity most days

- Managing stress levels

- Not smoking

- Taking your medication(s) as directed and managing other conditions

In addition to lifestyle changes, treatments often include medications and/or procedures. Talk with your doctor about which blood thinner is right for you. Keep in mind that if you take a blood thinner, you must be very cautious about falls and other accidents that might cause bleeding.

- Electrical cardioversion – uses low-voltage electrical shock applied to the chest with paddles to restore a normal rhythm

- Catheter-based ablation – a tube is inserted into a vein in the leg and threaded to the heart to fix the faulty electrical signals

- Surgical maze – small scar lines are made on the heart, creating a “maze” to prevent or redirect the abnormal beats from controlling the heart. This is done through open heart surgery.

- Pacemakers or atrial defibrillators – implantable devices that help restore and maintain regular heart rhythm

If you live with AFib, it’s critical that you know the warning signs of stroke so that you can act fast. Call 9-1-1 right away if you have any sudden:

- Numbness or weakness in your face, arms, or leg, especially on one side of the body

- Trouble walking or loss of balance or coordination

- Trouble seeing out of one or both eyes

- Confusion, trouble speaking or understanding

- Severe headache

Be sure other people in your life are aware of these signs as well.

It can be unsettling to live with AFib, especially if you can physically feel your heart beating unevenly. Be sure to share any concerns with your care team, especially how to manage your risk for stroke.

Here are some questions you may want to ask:

- What type of AFib do I have? Will I have it forever?

- What’s the difference between medications that control heart rhythm and those that control heart rate? Which one might be better for me and why?

- How serious is my risk for stroke?

- Which blood thinner is best for me?

- How else can I lower my risk of stroke?

- Are there changes I can make in my everyday life to prevent episodes of AFib?

- What type and how much exercise should I be getting?

- At what point should I consider a device or surgical procedure?

Atrial Flutter

Atrial flutter occurs when rapidly firing electrical signals cause the muscles in the heart’s upper chambers (atria) to contract quickly. This leads to a steady, but overly fast, heartbeat. Someone with atrial fibrillation (AFib or AF) can also have atrial flutter. But it’s also possible to have atrial flutter without another arrhythmia.

Atrial flutter may reveal itself in heart palpitations or a heartbeat that’s irregular or overly fast. Other symptoms of atrial flutter include:

- Fast, steady pulse

- Chest pain (angina)

- Shortness of breath

- Dizziness

- Lightheadedness

- Fainting (syncope)

- Heart palpitations

- Irregular heart rhythm combined with AFib

If you experience these symptoms and think you may be suffering from atrial flutter, contact your doctor immediately.

People who experience atrial flutter often have other conditions as well, including:

- Heart failure

- Previous heart attack

- Open-heart (bypass) surgery

- Other recent surgery

- Valve abnormalities or congenital defects

- High blood pressure

- Atrial fibrillation (AFib or AF)

- Thyroid dysfunction

- Alcoholism (especially binge drinking)

- Chronic lung disease

- Diabetes

- Other serious illness

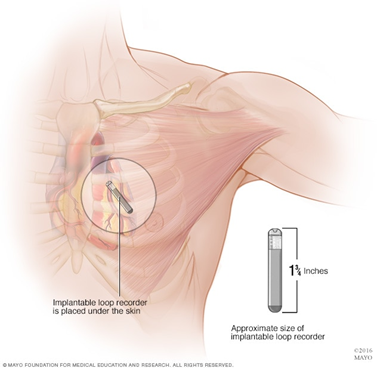

Implantable Loop Recorder

An implantable loop recorder is a type of heart-monitoring device that records your heart rhythm continuously for up to three years. It records the electrical signals of your heart and allows remote monitoring by way of a small device inserted just beneath the skin of the chest.

An implantable loop recorder can help answer questions about your heart that other heart-monitoring devices don’t provide. It allows for long-term heart rhythm monitoring. It can capture information that a standard electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG) or Holter monitor misses because some heart rhythm abnormalities occur infrequently.

For example, if you have a standard ECG to help figure out why you’re having fainting spells, it will only record any related heart rhythm abnormalities during the few minutes of the monitoring period — usually about five minutes. Because an implantable loop recorder monitors your heart signals for a much longer time, it’s more likely to capture what your heart is doing during your next fainting spell. This information may help your doctor make a definite diagnosis and develop a treatment plan.

Implantable loop recorders are one of the newer heart-monitoring devices. Researchers have evaluated their safety and benefit over the last 10 years. A study of 579 people with fainting spells showed that implantable loop recorders had a higher rate of diagnosis of heart rhythm problems than did other monitoring devices.

Researchers also examined the value of implantable loop recorders in people who had a stroke. Long-term heart monitoring uncovered heart rhythm problems that caused the stroke better than 24-hour monitoring did. Doctors used these results to guide treatment with blood-thinning drugs (anti-coagulation therapy) to prevent another stroke.

You will need to undergo a minor surgical procedure to place the implantable loop recorder. Risks of the procedure include infection or a reaction to the device that causes redness at the incision site.

You don’t need to do anything special to prepare for this procedure.

The procedure to insert the heart monitor is usually done in a doctor’s office, with a local anesthetic. Your doctor makes a tiny incision, inserts the device, which is smaller than a key or a thumb drive, and closes the incision. The device stays in place for up to three years.

The procedure to insert an implantable loop recorder has some risk because it involves minor surgery. Your care team will advise you to watch your incision for signs of infection and, perhaps, to limit activities until the wound heals.

The device records the electrical impulses of your heart and transmits them automatically to your doctor by way of the internet and wireless technology.

All you need to do is keep the transmission monitor your doctor gives you beside your bed. Transmissions occur while you’re asleep. You can also activate the data transmission process yourself. In addition, your doctor may ask you to keep a diary of your symptoms.

Your doctor will interpret the results of your test and call you if he or she has any concerns. You’ll likely need to see your doctor once or twice a year for routine checkups while the device is in place.

An implantable loop recorder is invisible and doesn’t interfere with your daily activities. It has no patches or wires, and you don’t have to worry about getting the device wet while bathing or swimming. These devices are supposed to be safe for use during a medical imaging procedure called magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), but let your doctor know about your implant before you schedule such a test.

It’s also possible an implantable loop recorder might set off metal detectors, for example, at an airport. Your doctor can provide you with a device identification card to carry with you for such situations.

Pacemakers (Device Therapy)

A pacemaker is a small, battery-operated device that helps the heart beat in a regular rhythm. There are two parts: a generator and wires (leads).

- The generator is a small battery-powered unit.

- It produces the electrical impulses that stimulate your heart to beat.

- The generator may be implanted under your skin through a small incision.

- The generator is connected to your heart through tiny wires that are implanted at the same time.

- The impulses flow through these leads to your heart and are timed to flow at regular intervals just as impulses from your heart’s natural pacemaker would.

- Some pacemakers are external and temporary, not surgically implanted.

Your doctor may recommend a pacemaker to make your heart beat more regularly if:

- Your heartbeat is too slow and often irregular.

- Your heartbeat is sometimes normal and sometimes too fast or too slow.

It replaces the heart’s defective natural pacemaker functions.

- The sinoatrial (SA) node or sinus node is the heart’s natural pacemaker. It’s a small mass of specialized cells in the top of the right atrium (upper chamber of the heart).It produces the electrical impulses that cause your heart to beat.

- A chamber of the heart contracts when an electrical impulse or signal moves across it. For the heart to beat properly, the signal must travel down a specific path to reach the ventricles (the heart’s lower chambers).

- When the heart’s natural pacemaker is defective, the heartbeat may be too fast, too slow, or irregular.

- Rhythm problems also can occur because of a blockage of your heart’s electrical pathways.

- The pacemaker’s pulse generator sends electrical impulses to the heart to help it pump properly. An electrode is placed next to the heart wall, and small electrical charges travel through the wire to the heart.

- Most pacemakers have a sensing mode that inhibits the pacemaker from sending impulses when the heartbeat is above a certain level. It allows the pacemaker to fire when the heartbeat is too slow. These are called demand pacemakers.

LIVING WITH YOUR PACEMAKER

If you’re living with an arrhythmia (erratic heartbeat), your doctor may have recommended a pacemaker to regulate your heart rate. You should also do your part to help your pacemaker control your heart rate. For example, if medications are a part of your treatment plan, be sure to take them as prescribed. Medications for arrhythmia work with your pacemaker and help to regulate your heartbeat.

It’s also good to keep records of what medications you take and when you take them. Download a printable medication tracker.

After you have your pacemaker implanted, your doctor will go over detailed restrictions and precautions. Make sure that you and your caregiver fully understand these instructions. Don’t be afraid to ask questions.

Before you leave the hospital, be sure to understand your pacemaker’s programmed lower and upper heart rate. Talk to your doctor about the maximum acceptable heart rate above your pacemaker rate.

Other considerations include:

- Allow about eight weeks for your pacemaker to settle firmly in place. During this time, try to avoid sudden movements that would cause your arm to pull away from your body.

- Avoid causing pressure where your pacemaker was implanted. Women may want to wear a small pad over the incision to protect from their bra strap.

- Relatively soon after your surgery, you may be able to perform all normal activities for a person of your age. Ask your doctor about how and when to increase activity.

Soon after your surgery, you may hardly think about your pacemaker as you go about your day. Just be sure to remember your doctor’s recommendations about daily activities. Bear in mind:

- Be physically active. Try to do what you enjoy – or what you feel up to – each day. Take a short walk, or simply move your arms and legs to aid blood circulation.

- Don’t overdo it. Quit before you get tired. The right amount of activity should make you feel better, not worse.

- Feel free to take baths and showers. Your pacemaker is completely protected against contact with water.

- Car, train, or airplane trips should pose no danger.

- Stay away from magnets and strong electrical fields. Learn more about how devices can interfere with ICDs and pacemakers.

- Tell your other doctors, dentists, nurses, medical technicians, and hospital staff members that you have a pacemaker.

- People with pacemakers can continue their usual sexual activity.

- Remember your pacemaker when you arrive at the airport or other public places with security screening. Metal detectors won’t damage your pacemaker, but they may detect the metal in your device. At the airport, let the TSA agent know that you have a pacemaker. You may need to undergo a separate security procedure, such as screening with a hand wand.

Download a free pacemaker wallet ID card. Showing it to personnel at places with metal detectors or other security screening devices may save you some inconvenience.

Modern pacemakers are built to last. Still, your pacemaker should be checked periodically to assess the battery and find out how the wires are working. Be sure to keep your pacemaker checkup appointments. At such appointments:

- Your doctor will make sure your medications are working and that you’re taking them properly.

- You can ask questions and voice any concerns you may have about living with your pacemaker. Make sure you and your caregiver understand what your doctor says. It’s a good idea to take notes.

- Your doctor will use a special analyzer to reveal the battery’s strength. This diagnostic tool can reveal a weak battery before you notice any changes.

Eventually, the battery may need to be replaced in a surgical procedure. This replacement procedure is less involved than the original surgery to implant the pacemaker. Your doctor can tell you about the procedure when the time comes.

Your doctor may recommend that you take and record your pulse often to gauge your heart rate. This allows both of you to compare your heart rate to your acceptable range to determine if your pacemaker is working effectively.

When taking your pulse at home, follow your doctor’s instructions about when to get in touch. In general, there’s no reason to contact your doctor unless:

- Your heart is beating faster than 100 beats per minute.

- Your heart rate suddenly drops below the accepted rate.

- Your heart rate increases dramatically.

- Your pulse is rapid and irregular (above 120 beats per minute) and your pacemaker is programmed for a fast-slow type of heartbeat.

- You notice a sudden slowing of your heart rate.

Don’t worry if your heart is beating close to or within the intended heart rate, but has an occasional irregularity. It likely just means that your heart’s natural pacemaker is competing with the signals emitted by the artificial pacemaker. This occurs infrequently, but it’s normal.

Contact your doctor immediately if:

- You have difficulty breathing.

- You begin to gain weight and your legs and ankles swell.

- You faint or have dizzy spells.

Carry a card that alerts healthcare workers in case you’re unable to tell them about your pacemaker. Keep it in your wallet, purse or phone case so that it’s always with you. Download a printable pacemaker wallet ID card. In case of an accident, emergency personnel need to know that you have a pacemaker implanted. For example, medical personnel should know about your pacemaker before ordering diagnostics involving an MRI, which is among the devices that may interfere with your pacemaker.

You can also consider an ID bracelet or necklace for added security and convenience.

Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (CRT)

If you have heart failure and have developed arrhythmia, you may be a candidate for cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT).

Arrhythmias are irregular heart rhythms and can be caused by a variety of reasons, including age, heart damage, medications, and genetics. In heart failure patients, CRT, or biventricular pacing, is used to help improve the heart’s rhythm and the symptoms associated with the arrhythmia.

The procedure involves implanting a half-dollar sized pacemaker, usually just below the collarbone. Three wires (leads) connected to the device monitor the heart rate to detect heart rate irregularities and emit tiny pulses of electricity to correct them. In effect, it is “resynchronizing” the heart.

Because CRT improves the heart’s efficiency and increases blood flow, patients have reported alleviations of some heart failure symptoms, such as shortness of breath. Clinical studies also suggest decreases in hospitalization and morbidity as well as improvements in quality of life.

In general, CRT is for heart failure patients with moderate to severe symptoms and whose left and right heart chambers do not beat in unison. However, CRT is not effective for everyone and is not for those with mild heart failure symptoms or diastolic heart failure or who do not have issues with the chambers not beating together. It is also not suitable for patients who have not fully explored correcting the condition through medication therapies. To date, studies show CRT to be equally effective for both men and women.

Talk with your doctor about your own suitability for CRT. They can take into account your unique medical history as well as age and desired level of intervention. CRT is also often combined with other treatments to achieve the best results.

Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD)

Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators (ICDs) are useful in preventing sudden death in patients with known, sustained ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation. Studies have shown ICDs to have a role in preventing cardiac arrest in high-risk patients who haven’t had, but are at risk for, life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias.

Newer-generation ICDs may have a dual function which includes the ability to serve as a pacemaker. The pacemaker feature would stimulate the heart to beat if the heart rate is detected to be too slow.

An ICD is a battery-powered device placed under the skin that keeps track of your heart rate. Thin wires connect the ICD to your heart. If an abnormal heart rhythm is detected the device will deliver an electric shock to restore a normal heartbeat if your heart is beating chaotically and much too fast.

ICDs have been very useful in preventing sudden death in patients with known, sustained ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation. Studies have shown that they may have a role in preventing cardiac arrest in high-risk patients who haven’t had, but are at risk for, life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias.

The American Heart Association recommends that before a patient is considered to be a candidate for an ICD, the arrhythmia in question must be life threatening, and doctors have ruled out correctable causes of the arrhythmia, such as:

- Acute myocardial infarction (heart attack)

- Myocardial ischemia (inadequate blood flow to the heart muscle)

- Electrolyte imbalance and drug toxicity

Because many people do not understand their underlying condition – such as heart failure or genetic predisposition for risk of sudden cardiac arrest – and because ICDs are used primarily to prevent sudden cardiac death, they in turn may not understand the benefits versus the limitations of having an ICD implanted. If you are one of those people, you will find information and guidance here.

Your doctor may recommend an ICD if you or your child is at risk of a life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia because of having:

- Had a ventricular arrhythmia

- Had a heart attack

- Survived a sudden cardiac arrest

- Long QT syndrome

- Brugada syndrome

- A congenital heart disease or other underlying conditions for sudden cardiac arrest

A battery-powered pulse generator is implanted in a pouch under the skin of the chest or abdomen, often just below the collarbone. The generator is about the size of a pocket watch. Wires or leads run from the pulse generator to positions on the surface of or inside the heart and can be installed through blood vessels, eliminating the need for open-chest surgery.

It knows when the heartbeat is not normal and tries to return the heartbeat to normal.

- If your ICD has a pacemaker feature when your heartbeat is too slow, it works as a pacemaker and sends tiny electric signals to your heart.

- When your heartbeat is too fast or chaotic, it gives defibrillation shocks to stop the abnormal rhythm.

- It works 24 hours a day.

New devices also provide “overdrive” pacing to electrically convert a sustained ventricular tachycardia (fast heart rhythm) and “backup” pacing if bradycardia (slow heart rhythm) occurs. They also offer a host of other sophisticated functions such as storage of detected arrhythmic events and the ability to perform electrophysiologic testing. Stored information can help your doctor optimize the ICD for your needs.

LEARN MORE ABOUT LIVING WITH YOUR ICD

It is important for you to be aware that an ICD does not change the underlying condition that leads to implantation of it. Whether due to heart failure or genetic risk for sudden cardiac arrest, an ICD is implanted to help prevent sudden cardiac arrest.

While using an ICD does not reverse heart disease or alter a gene, it does reduce your risk of cardiac arrest. You should also follow your doctor’s instructions for treating your underlying conditions.

Medications are part of your treatment plan that includes your ICD, so take medications exactly as instructed.

- Medications work with your ICD and help your heart pump regularly.

- Keep records of what medications you take and when.

- Make sure you understand your device and all instructions.

- Your ICD should be checked regularly to find out how the wires are working, how the battery is doing, and how your condition and any external devices have affected the ICD’s performance.

- Your doctor may check your ICD several times a year by office visit, over the phone, or through an internet connection.

- ICD batteries last 5 to 7 years.

- Your doctor uses a special analyzer to detect the first warning that the batteries are running down, before you can detect any changes yourself.

- Eventually your ICD or battery may need to be replaced in a surgical procedure. The replacement procedure is less involved than the original implantation procedure. Your healthcare provider can explain it to you.

- Feel free to take baths and showers. Your ICD is completely protected against contact with water.

- Stay away from magnets and strong electrical fields, and inform airport or other screeners that you have an ICD.

- Tell your other doctors, nurses, medical technicians, hospital staffs, and dentists that you have an ICD.

- Follow the restrictions on activity and any other recommendations from your healthcare professional.

- Allow about eight weeks for your ICD to settle firmly in place. During this time, avoid sudden, jerky, or violent actions that will cause your arm to pull away from your body.

- Avoid causing pressure over the area of your chest where your ICD was put in.

- Women may find it more comfortable to wear a small pad over the incision as protection from their bra strap.

- Car, train, or airplane trips should pose no danger. However, on rare occasions, ICDs have caused unnecessary shocks during long, high-altitude flights.

- You cannot drive commercially when you have an ICD.

- While you can probably drive about a week after your implantation surgery, your doctor will be the one to give you a green light. If you received an ICD due to certain conditions – such as having had sudden cardiac arrest or fainting – your doctor may ask you to wait until several months after you last fainted before driving again. Fainting is a possibility even after implantation of an ICD.

- Be physically active every day. Do whatever you enjoy – take a short walk or just move your arms and legs to help your circulation.

- Ask your healthcare professional about how and when to increase activity. Typically, you should wait one month at least before lifting heavy items or doing any high-impact activity. Ask your physician about engaging in full-contact sports that could damage or dislodge your ICD or wires.

- You may be able to perform all of your normal activities within a few days of surgery other than the heavy lifting and high-impact activities as mentioned previously. Once your physician allows it, you can probably even return to strenuous activities. Always ask your doctors.

- Don’t overdo it — quit before you get tired. The proper amount of activity should make you feel better, not worse.

-

Don’t leave home without it.

- Always keep it with you in case of accident so emergency personnel can treat you appropriately.

- Security devices in public places may detect the metal in your ICD, although they won’t damage it. Showing your card may save you some inconvenience.

- Consider also getting an I.D. bracelet or necklace for additional security and convenience.

-

After ICD implantation, you may feel anxious or depressed. This is not uncommon for ICD recipients, especially in the first months or year after implantation. Unfortunately, it is uncommon for patients to seek help for their anxiety and depression. If you experience these feelings, or even anticipate them, consult with your doctor or healthcare team and get help.

There is no reason to feel embarrassed by or alone with your feelings. By asking questions and expressing your concerns about the ICD and your reactions to it, you might prevent or alleviate potential anxiety or depression.

Exposure to a traumatic life-or-death experience is a key to diagnosing PTSD. You may not think of yourself as having PTSD, but having sudden cardiac arrest, multiple shocks, or other near-death situations can certainly bring about PTSD symptoms. Do not hesitate to discuss your feelings regarding the trauma with your healthcare team. Your mental and emotional well-being is important to your physical well-being.